VIETNAM AIR LIFT

The intractable war in Vietnam didn’t end with the ‘peace with honour’ claimed by US President Richard Nixon and his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger but in outright victory for the communist North Vietnamese. And with it concluded Freemantle’s career as a foreign correspondent amid storms of criticism and controversy at an enterprise he considered the highlight of that career.

Freemantle’s first Vietnam assignment in February, 1971, marked the near total disillusionment with a war openly expressed by US troops on the ground and continuous public protest and opposition on American streets: one estimate was that two thirds of disaffected US servicemen returned from their nine month Vietnam rotation afflicted with drug problems, many seriously addicted. A journalistic meeting place was the expansive, open-sided verandah of the Continental Hotel, next to the South Vietnamese parliament building. From there Freemantle nightly watched glassy-eyed, zombie-shuffling servicemen stumbling up and down Tu Do, Saigon’s main street, in drug-induced oblivion from where they were and what they were being ordered to do. The processions continued for two years, while Kissinger and the North Vietnamese shuffled even more slowly to agree a ceasefire. Months were taken up simply reaching a diplomatically acceptable shape for the negotiating table around which they were to sit to avoid either side appearing the victor or the vanquished. Hundreds more Americans and thousands more Vietnamese died while tables were re-arranged and chairs repositioned.

Freemantle was back in Vietnam in 1973, on Highway 13 between Saigon and Tay Ninh, to witness the precise moment peace was officially supposed to end the fighting to triumphant celebrations in Washington and champagne toasts in Paris, where the protracted negotiations had straggled on. An immaculately tailored South Vietnamese colonel, his uniform completed by a gold tipped, ivory swagger stick, had just predicted to Freemantle that the communists of breaking the supposed ceasefire when, as if on cue, a Vietcong squad embedded in a bordering rice paddy staged their ambush. Freenantle fled for the protection of an elevated embankment levee – wrongly into,  not away from, the machine and automatic weapon fire and lay, momentarily spread-eagled like a funfair targets on the raised bank. Miraculously, the bullets missed although one shattered a stone that cut his face. Freemantle used that experiences as a background for RULES OF ENGAGEMENT, published in America as THE VIETNAM LEGACY.

not away from, the machine and automatic weapon fire and lay, momentarily spread-eagled like a funfair targets on the raised bank. Miraculously, the bullets missed although one shattered a stone that cut his face. Freemantle used that experiences as a background for RULES OF ENGAGEMENT, published in America as THE VIETNAM LEGACY.

It was to take another two years and cost hundreds more lives before the North Vietnamese victoriously entered Saigon to the frenzied panic of South Vietnamese terrified of the imprisonments and political re-education camps that were to follow. Western aid workers and organizations were just as desperate to protect those for whom they’d cared in South Vietnam throughout the war. One such organization was an adoption society named Project Vietnam Orphan, which appealed for help rescuing children from its Saigon orphanage. It was Freemantle’s idea, backed by Daily Mail editor, Sir David English to mount that rescue.

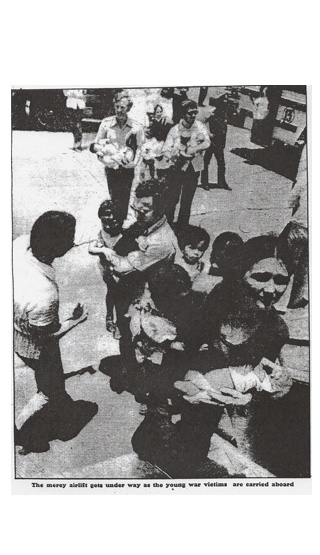

The only airline not to ridicule flying into a country about to lose a war was British Midland Airways, but the Daily Mail had to insure the aircraft: the company’s insurance did not cover it going into a war zone. By the end of the first day, a 707 had been leased, Save the Children Fund had agreed to supply doctors and nurses for the flight – a Daily Mail team already in Saigon warned that some of the orphans were ill – and contact made with a Lloyds of London aircraft insurance syndicate. By lunchtime the following day visas had been issued by the South Vietnamese embassy in London and an all male crew flown to Bombay for the rescue leg in and out of Saigon. At lunch that same day the insurance was negotiated: landing and departure times had to be stipulated, the escalator cover increasing by every hour the aircraft remained on the ground. South Vietnamese authorities in Saigon insisted the coaches transported the 100 children to Ton Son Knut airport before the overnight curfew was lifted to avoid people panicking – as they were later to do trying to scale the walls and gates of the American embassy – at an imagined exodus. The Vietcong, North Vietnamese guerilla fighters in the south, were believed to ring Ton Son Knut by the time the Daily Mail plane landed. Two days earlier an American-sponsored children’s rescue aircraft had crashed shortly after take-off. Engine malfunction was blamed but Freemantle refused to allow any Vietnamese airport workers near the aircraft. The orphan’s coaches missed the ending of the curfew but the feared public panic did not materialize. South Vietnamese soldiers blocked the vehicles at the airport gates, though, stranding the children in scorching midday heat. They blocked the entrances to washrooms, too, demanding $50 in US currency for water to relieve the orphans’ dehydration. It was almost an hour before the coaches were finally negotiated through the gates and on to the aircraft. Daily Mail reporters and cameramen were offloaded at refueling stops at Bombay and Dubai to file the account of the rescue. The rescue mission from London take-off to London return took 36 hours.

In that time the attacks from other British media, motivated by some to whom the idea of a British rescue hadn’t occurred, had become hysterical. One label was The Daily Mail Baby Snatch Airlift. Another open accusation was that they had been kidnapped. Supposed child care professionals were eagerly quoted criticizing the removal of children from their own cultural environment.

In 2010, at her specific request, Freemantle met for the first time Viktoria Cowley, the Anglicized name of the beautiful Vietnamese woman he’d brought out of Vietnam as an 18 month old baby on the Daily Mail rescue flight. She told him: ‘You saved my life and those of every other child. On their behalf and my own, thank you.’

Brian Freemantle: The Saigon Mission

Also here is a link to the BBC article