THE NEWSPAPER YEARS

During his newspaper career Freemantle travelled and worked in 30 countries, including the United States, Russia, Vietnam, India, the Middle East, Latin America and the European Union. And throughout that time wrote books, nursing an ambition one day to become a full time author. In every foreign city, when his journalistic assignments allowed, he rode tourist buses, took guided trips and collected street maps and memorabilia for potential settings for as then unwritten, unconceived novels. Following that routine, he completed 16 full length manuscripts – eight written on commuter trains to London during his periods in England – and had each rejected by every English publisher to whom they were submitted.

The 17th, GOODBYE TO AN OLD FRIEND, was contracted in five countries in as many months and bought – although never made – for a film. It was, ironically, set predominantly in England although its lead Russian characters were drawn from people he’d encountered as a journalist in Moscow. The fictionally depicted spies were modeled on genuine intelligence agents working as diplomats in London’s then KGB-dominated Polish and Hungarian embassies. Independently they approached Freemantle with blackmail-entrapping financial offers to act for them – in spookspeak, as an agent of influence – by writing communist-slanted articles in the London Daily Sketch and Daily Mail, for both of which he worked as Foreign Editor as well as overseas correspondent.. Both approaches were rejected.

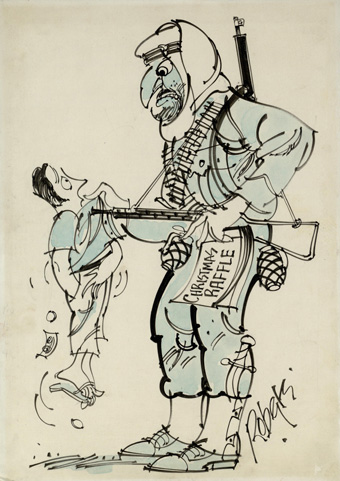

The background authenticity for both BETRAYAL and MISFIRE came from a period Freemantle spent in Amman when King Hussein of Jordan came close to losing control of his country to the Palestinian Liberation Organization. Within Jordan its terrorist wing was known as Saiqua. From it Freemantle obtained a “passport” illegally to travel, unhindered by official authorities, between Jordan and the Syria’s capital, Damascus to get a World-exclusive interview with the then PLO leader Yasser Arafat. Freemantle’s discovery how the PLO extorted money from intimidated foreign tourists – camouflage uniformed “freedom fighters” complete with Kalashnikov AK47s and grenade bandoliers touting raffle tickets for which there were no prizes at Lebanese hotels in neighbouring Beirut – was edited out of an early draft of BETRAYALS, but gained this cartoon in the London Daily Express for the feature he wrote of his personal encounter with a fully armed ticket seller in the Lebanese capital’s King George hotel. (include here Boston-supplied cartoon.)

Not every journalistic experience translated directly into material for a book. In 1971, during the war that divided East and West Pakistan and led to the creation of Bangladesh as an independent state, Freemantle once more bypassed official entry procedures to get into East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. To do so he traveled 450 miles by car, once-a-week village bus, on foot and dug-out canoe across the vast island-and-river water world created by the huge Ganges river before it eventually enters the sea. It was a trek halted by East Pakistan villagers fleeing shoot-on-sight soldiers of West Pakistan then leader Yahya Khan and whose ethnic cleansing gunfire was clearly audible less than a mile behind. He would be killed, the villagers insisted: no eye witnesses of the genocide were being spared and as a Westerner he was a greater target than they were. Freemantle fled with the villagers.  The pursuit lasted three hours before the refugees split from him, terrified that their vulnerability was heightened by association with him. It was the villagers who left more visibly obvious tracks that the soldiers followed. Their gunfire persisted. for a while longer. Then it abruptly went quiet.

The pursuit lasted three hours before the refugees split from him, terrified that their vulnerability was heightened by association with him. It was the villagers who left more visibly obvious tracks that the soldiers followed. Their gunfire persisted. for a while longer. Then it abruptly went quiet.

It would be ill fitting for Freemantle ever to imagine a fictional setting for his real life encounter with Mother Theresa. But he’s never forgotten the devotion-inspired equanimity with which she met mind-numbing official bureaucracy. At least three million East Pakistanis fled into Indian, bringing with them a cholera epidemic that quickly engulfed India in a pandemic that killed hundreds of thousands. It was a catastrophe that gained world wide attention and international aid efforts through the pictorial brilliance of Daily Mail photographer Norman Potter.  The cholera victims had two overwhelming needs, plastic sheeting for their improvised shelters from the incessant monsoon rains and immediate anti-cholera inoculation. Freemantle was at Calcutta’s Dum Dum airport – at the bottom of the main runway of which hundreds of stricken sufferers were camped in the open - when an Australian C130 cargo plane touched down carrying just such a life saving cargo touched down. Its Australian crew at once began unloading, asking for airport ground staff help and transportation. Which was refused. There had been no official notification from the capital, New Delhi, of the Australian’s intended arrival: their cargo could not be accepted. Thousands of doses of anti-cholera vaccine cooked in the heat: the plastic sheeting softened into solid, useless heaps. Only Mother Theresa remained calmly controlled during the close-to-blows confrontation after even she failed to persuade a change of Indian attitude. It was the way of India, the way of God, which defied human conception. And, she added tellingly, India had been taught its bureaucracy by the British in the days of the raj. It was not Mother Theresa’s first experience of such intransigence during the cholera disaster. Nor Freemantle’s. Two days earlier 40 RAF marquees, each capable of housing 200 people, had arrived at the same airport as a gift from Singapore, addressed to “the government of India.” The address should have been “the government of West Bengal.” The impasse lasted 48 hours before West Bengal’s Chief Minister and refugee officials personally visited the airport to sign for the acceptance of the consignment. They left imagining the aid would finally be released to the huddled refugees within sight of the airport.

The cholera victims had two overwhelming needs, plastic sheeting for their improvised shelters from the incessant monsoon rains and immediate anti-cholera inoculation. Freemantle was at Calcutta’s Dum Dum airport – at the bottom of the main runway of which hundreds of stricken sufferers were camped in the open - when an Australian C130 cargo plane touched down carrying just such a life saving cargo touched down. Its Australian crew at once began unloading, asking for airport ground staff help and transportation. Which was refused. There had been no official notification from the capital, New Delhi, of the Australian’s intended arrival: their cargo could not be accepted. Thousands of doses of anti-cholera vaccine cooked in the heat: the plastic sheeting softened into solid, useless heaps. Only Mother Theresa remained calmly controlled during the close-to-blows confrontation after even she failed to persuade a change of Indian attitude. It was the way of India, the way of God, which defied human conception. And, she added tellingly, India had been taught its bureaucracy by the British in the days of the raj. It was not Mother Theresa’s first experience of such intransigence during the cholera disaster. Nor Freemantle’s. Two days earlier 40 RAF marquees, each capable of housing 200 people, had arrived at the same airport as a gift from Singapore, addressed to “the government of India.” The address should have been “the government of West Bengal.” The impasse lasted 48 hours before West Bengal’s Chief Minister and refugee officials personally visited the airport to sign for the acceptance of the consignment. They left imagining the aid would finally be released to the huddled refugees within sight of the airport.  It wasn’t. In the judgment of the airport Customs hierarchy the Chief Minister did not qualify as a member of the West Bengal government. “There are official forms. Things have to be done properly,” explained a spokesman. It was another three days before the tents were freed. Hundreds more died in that time.

It wasn’t. In the judgment of the airport Customs hierarchy the Chief Minister did not qualify as a member of the West Bengal government. “There are official forms. Things have to be done properly,” explained a spokesman. It was another three days before the tents were freed. Hundreds more died in that time.

Freemantle continued to roam the world when he quit full time journalism in 1975 to write full time. For his fiction-based-on-fact book HMS BOUNTY, in which he suggested a hitherto unknown reason for the world’s most famous mutiny, Freemantle succeeded in getting to one of the remotest and inaccessible places in the World, the South Pacific island of Pitcairn, upon which all but one of the mutineers settled to evade justice. That exception, after years of self-imposed exile, was ringleader Fletcher Christian, with whose descendant Freemantle lived on the island. From conversations with those mutineer descendants – one who regarded himself the historian of the mutiny and its aftermath - Freemantle speculated the never-before revealed reason for the mutiny. And that after years on Pitcairn, Fletcher Christian escaped on a passing whaler to return to his Cumbria birthplace.

Freemantle went under cover with American government agents in Colombia to research his non fiction book THE FIX, in which he identified, by name and sometimes residential addresses, the billionaire drug lords even then, as now, masterminding the worldwide supply of cocaine One, Jose O’Campo, took out a contract on Freemantle’s life during a publicity tour throughout America in 1986. America’s FBI discovered the attack was planned for Florida. That segment of the book promotion was cancelled but throughout the rest of the tour there were persistent attempts from people falsely claiming to be book reviewers and columnists to get advance details of Fremantle’s itinerary to carry out the attack.The details were never disclosed and the tour was completed. Payment for a successful hit was to have been a kilo of pure cocaine.

All Freemantle’s requests for a Russian entry visa were refused after 1982, the year he published KGB, an expose of the then Soviet intelligence service who actually stole the only advance copy of the book from its display stand at the Frankfurt Book Fair that year. Ironically, two years later in Japan, Freemantle signed a commemorative register recording the 100,000 sale of KGB directly beneath the signature of exiled Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Freemantle’s ban from Russia was lifted after Mikhail Gorbachov came to power and introduction perestroika and glasnost.

The majority of Freemantle’s books have an espionage background, to establish the factual accuracy of which he has received guidance from operatives at the highest echelons of English, Russian, and American intelligence. In England that help came from Sir Dick White, the only man ever to have headed both Britain’s external intelligence service, MI6, and its internal counterpart, MI5. The now retired KGB general who consistently helped on at least ten separate novels devised the 1978 assassination of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov on London’s Waterloo Bridge, having the killer implant a ricin-tipped poison capsule into Markov’s thigh from an umbrella tip. Legendary CIA spy-catcher James Jesus Angleton hosted dinner for Freemantle at Washington’s Army and Navy Club at the permanently reserved table at which he openly accused Kim Philby, head of Britain’s MI6 Russian desk, of being a long time KGB spy. To which Philby dismissively jeered that he had been a KGB agent since his Cambridge university days. Philby’s reaction threw Angleton off the scent for a further six months, by which time Philby had defected to Moscow to be promoted to the rank of KGB general.

What happened to real life espionage at the end of the Cold War in 1991 Contrary to the doubtful wisdom of British and American publishing houses, spying didn’t end with it. It actually increased: in the first year after the supposed thaw, the budget of the CIA doubled. What switch there was occurred in the methodology: quantum strides in technology meant there is now a greater information gathering reliance on ‘sigint’ – signals and electronic interception – and less upon ‘humint’, agents on the ground. It surprised a lot of ‘spying is over’ doomsayers in 2010 when it emerged that 22 Russian espionage agents swept up in and around New York communicated through the traditional tradecraft of dead letter boxes, brush contact for package exchanges and chalk marked signaling. Their arrest, though, came through computer interception.

And those 16 early rejected books Freemantle’s greatest professional regret – as well as justifiable embarrassments – is that in a fit of rejection depression and needing to fit the contents of a large Victorian house into a small garden development, he burned them. It was a Philistine act, worsened by the later invitation from the Howard Gottlieb Memorial Library in Boston, Mass, to be the archival repository of all his written material. None of the 16 deserved publication or reworking: that’s why they were rejected by so many different publishers. Their value to Boston. would have been to illustrate the gradual progression from amateur author beginner to the moment of publication, a progression that has so far reached a total of 87 books, with more in the pipeline. ,

The Cartoon which appeared in the Daily Express during Freemantle's reporting of the El Fatah attempted stranglehold on Jordan. It depicts an encounter on the terrace of Beruit's legendary King George Hotel where Freemantle's lunch was interrupted by El Fatah fighters, complete with Kalashnikov semi automatic Rifles and grenade bandaliers selling raffle tickets to raise funds for their war chest.That night Freemantle "joined" the Syrian Terrorist organisation 'Saiquai' to get into Damascus for a world exclusive interview with El Fatah leader Yasser Arafat.